The Recent Movement of Bengali Poetry and New Poetry

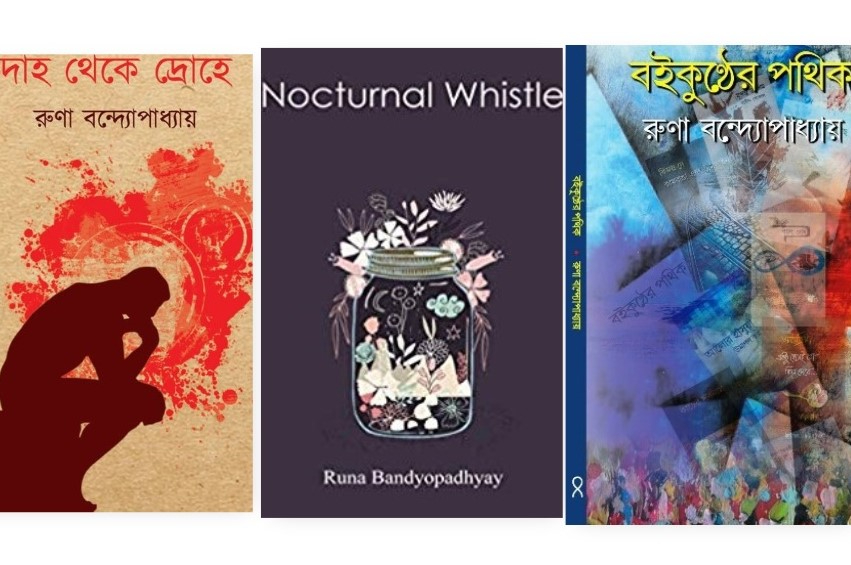

By Barin Ghosal & Translated by Ms. Runa Bandyopadhyay

Everyday around hundred movements, with right and claims of oppositions, take place in Bengal so that the word ‘movement’ has lost its charm. Monkeys make movements on the trees. What’s the movement of poet again? The word is not suitable for literary or poetry at all.

In my view, there has been pure movement in the Bengali society after independence, so far only two in the sixties. The first one is the Hungry movement[1] and the second one is the Naxalite movement[2]. Anything less than that cannot be called as movement. The state machinery suppressed both of them at that time. However, its shadow remained in our thought and application, for fifty years. You can learn about many other movements of sixties, seventies or eighties from history books. But I do not know that those movements meant for whose comfort. In that sense, the emergence and expansion of the ‘New Poetry’ is not a movement. This is definitely ‘Other Poetry’, but there was no claim or opposition in front of or behind it. Therefore, that was not a movement. Movement – what I understood by the word is that it was a vibration or oscillation due to the emergence of ‘Other’, which became prolonged. I will proceed with this ‘understanding’ from now onwards, because, that was what exactly happened.

Remember the twenties or thirties era of the last century, when the concept of modern poetry was germinating. Any poetry written at that time or any other time was not called as modern poetry. It had a different definition. Likewise, a poem written recently cannot be called as ‘New Poetry’, because it has its own definition too. In a plain language I could say, the poetry without the attributes of ‘Old Poetry’ will be called as ‘New Poetry’. This announcement has no copyright, no patent. Anyone can complain against it, anyone can take away its importance and greatness. However, the poets usually refrain from this abusive process.

Accepting the supremacy and richness of traditional Bengali poetry, I could say, although some personal poems had been sparkled, but in general, the best poems of the time had been imitated. It was observed that the unintelligent poets were following or imitating the great Noble laureate Rabindranath Tagore[3]. After that since the sixties, imitating the poet Jibanananda Das[4] was going on, and the imitation had been imitated for a long time. In the middle of the seventies, when we started to write serious poems, we had to struggle in that ocean of joy! That time there was joy with everything, academy, clapping, media screaming and business dealings except the weeping for the sake of revolution. At the end of seventies, Kaurab[5] poets were at the last gasp. We thought – why should we write poetry? Who told us to write? What is the need to make those professional copying? If we have to write, we will write original poetry, which hasn’t been written yet. If we are not able to write, leaving this we will fly the kite or make the love affair. However, the original poetry does not descend from dreams, not even from a granted boon. That’s why it is necessary to pursue. It requires deep thoughts and practise. In search of that, we started the Poetry Camp. Its reports moved the Bengali society. The media started to copy it but failed. The poetry camp lasted for seven years from 1981 to 1987.

Read full prose at Dispatches Poetry War

[1] Hungry Movement – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hungry_generation

[2] Naxalite Movement – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naxalite

[3] Rabindranath Tagore – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rabindranath_Tagore

[4] Jibanananda Das – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jibanananda_Das

[5] Kaurab – A Bengali language literary magazine representing innovative, alternative, non-mainstream and experimental genres of Indian literature with an emphasis on poetry and poetics.